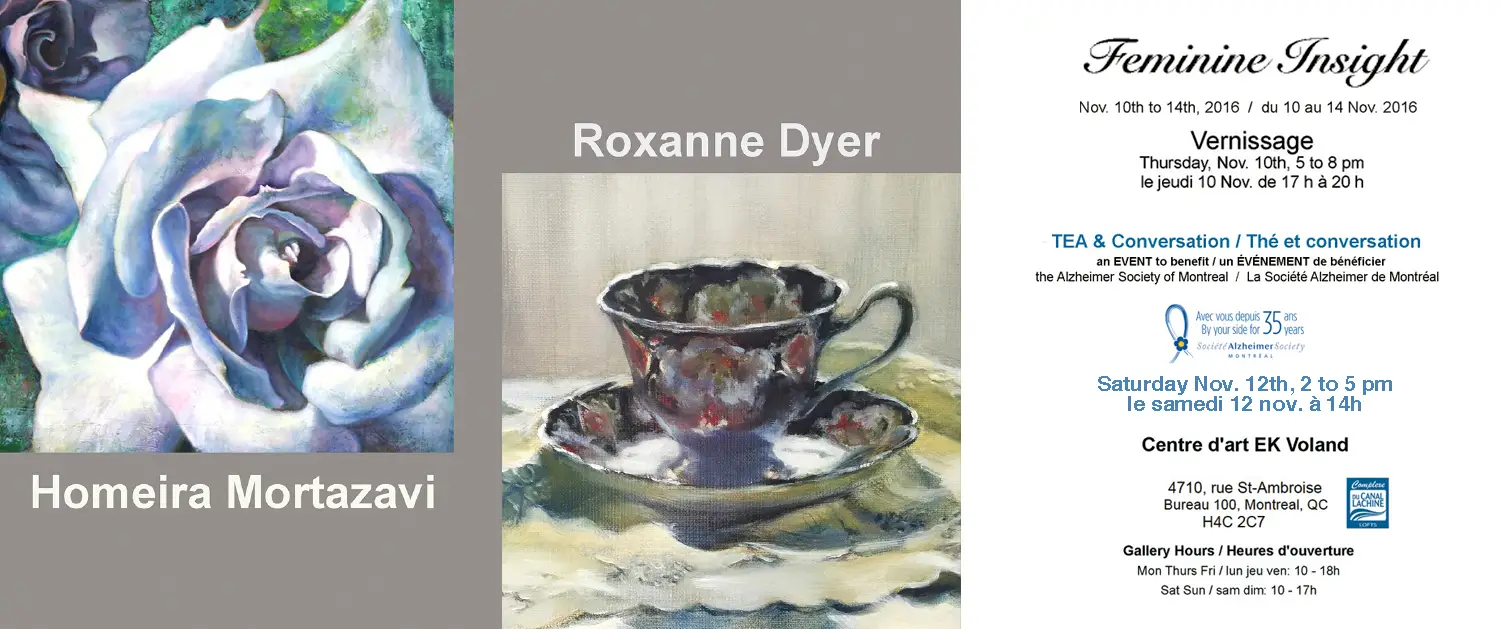

“Femisages”

Homeira Mortazavi démystifie la condition féminine avec ironie en l’esthétisant. Elle y parvient à travers une série d’œuvres que l’on pourrait appeler des paysages féminins ou des « fémisages », car celles-ci couvrent toute une gamme d’archétypes féminins, de la virginale Woman and White Roses à la Gipsy Bourgeois aux airs de fille de joie. De même, Mortazavi déboulonne sans retenue le mythe du corps féminin idéal dans Seated Woman. De plus, l’artiste parsème ses tableaux souvent baroques de métaphores visuelles […]

“Feminization”

Homeira Mortazavi ironically demystifies the feminine condition by aestheticizing it. She achieves this through a series of works that could be called feminine landscapes or "feminizations", because these cover a whole range of feminine archetypes, from the virginal Woman and White Roses to the Gipsy Bourgeois to the airs of a girl of joy. Likewise, Mortazavi unabashedly debunks the myth of the ideal female body in Seated Woman . In addition, the artist sprinkles his often baroque paintings with visual metaphors whose double meanings reveal more than it seems at first glance.

In this vein, The Box presents a frank vision of the “glass ceiling”, this obstacle to the professional advancement of women which is slow to be officially recognized. In Mortazavi's painting, the seemingly idyllic surroundings of the female figure engulf her, so that for all intents and purposes, "She is a bird in a golden cage." Despite her beautiful finery, the constraints and restrictions of this artificial paradise inexorably make it a prison for this woman. Almost crushed by the limitations imposed on her, she folds under a weight that she supports at arm's length. On her knees and without clothes, this woman has nothing left but her naked body. More precisely, in this painting, the naked female body is not a subject of desire, and even less a sexual object; rather, it constitutes a tool of liberation, a means of resistance and a weapon against the objectification of women, which the title The Box disturbingly implies. No wonder then that the body language of the female figure in the painting says a lot about the obstacles that remain to be overcome. Despite its great beauty, this painting depicts above all female struggles. In truth, this woman's ostensible optimism does not make her situation any less desperate. As in other paintings by Mortazavi, spectators perceive that here, the artist cleverly uses roses as a subterfuge to define the condition of women whose daily life, contrary to all appearances, is far from being rosy. In short, The Box happens to be a visual and feminist adaptation of the novel Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand.

Similarly, Mortazavi takes up mythological themes in the painting The Eternal Flame . Through feminist and pictorial storytelling, she presents both the biblical myth of Moses and the burning bush and the Greek myth of Prometheus. In relation to this first myth, Mortazavi makes the female figure the recipient of divine revelation; as for the second, this time it is the woman, rather than the man, who receives the divine gift of fire. Mortazavi thus expresses in unequivocal terms that the transmission of the sacred takes place through women. Mortazavi underlines this feminist perspective by situating the woman in a domestic setting energized by a surrealist touch, in a style reminiscent of Salvador Dali. This pictorial strategy has the effect of sanctifying the banality of the framework assigned to the woman as “queen of the home”.

Mortazavi continues her exploration of feminist spirituality in the painting Transcendent . Its ethereal depiction of the female body stands in stark contrast to the down-to-earth embodiment of women in the artist's other works. In fact, her resolutely figurative art finds its raison d'être in the female body as a cornerstone of feminism. However, Mortazavi avoids reducing the female condition to a material phenomenon. On the contrary, in Transcendent , she evokes the multidimensionality of women through the use of negative space to represent the female body, a pictorial strategy reminiscent of the surrealist René Magritte. Although imbued with reverie, Mortazavi's painting captures the male gaze, that is to say the representation of the woman from a male point of view by presenting her as an object subject to the pleasure of the man. In reality, Transcendent reverses the roles as the woman casts an inquisitive glance at the man.

In light of these considerations, Mortazavi's iconoclasm is evident: she shatters images of male hegemony and replaces them with visual narratives that provide a platform for a feminist perspective. When it comes to the representation of women in art, Mortazavi’s “feminizations” lift the veil on a two-sided mirror.

Professor Norman Cornett